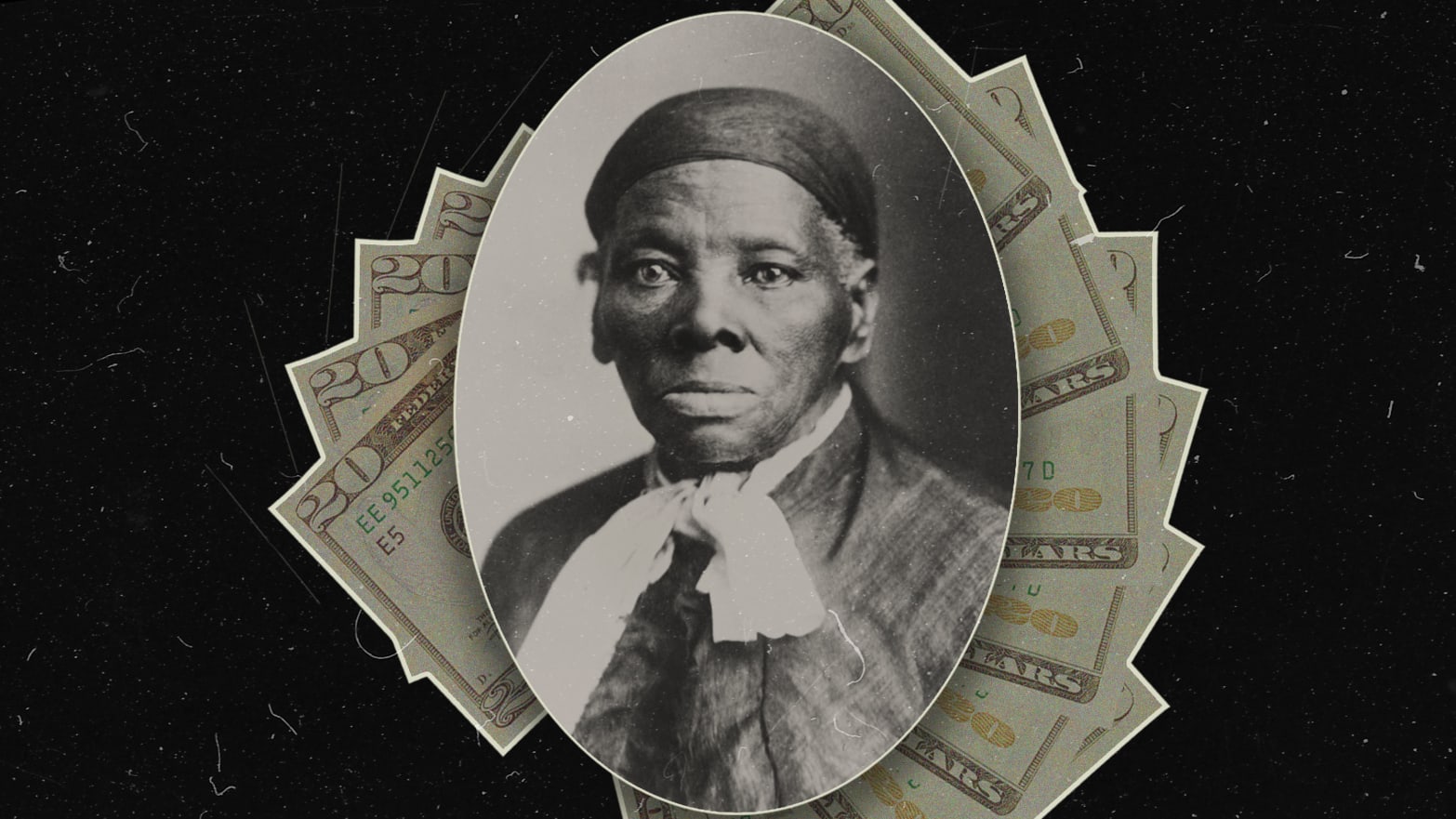

Picture Illustration by Erin O'Flynn/The Each day Beast/Getty

Certainly one of America’s most fervently held—and desperately clung to—myths is that our racial hierarchy is neither engineered nor rigorously enforced, however the pure and inevitable results of each group getting precisely what they deserve. On the core of this fictive concept is the assumption that the innately civilized, law-abiding, industrious, and clever nature of whiteness justifies its place atop the racial order, simply because the inherent pathology, criminality, ignorance, and self-defeating methods of Blackness perpetually constrain it to the underside. Of the myriad self-absolving and racist lies propagated by white supremacist tradition, the notion that Black of us have solely themselves guilty for his or her oppression is maybe essentially the most insidious. It’s a denialist view wholly divorced from each the results of American coverage and the realities of our previous, and its hegemony requires defensive upkeep of a nationwide reminiscence constructed on lies of historic omission.

This whitewashing occurs not simply symbolically, in textbooks, monuments, memorials, and markers, however materially, in insurance policies that instantly impression the life, demise and political energy of Black People. Affronted by Black emancipation and enfranchisement after shedding the Civil Battle, defeated Confederates developed the Misplaced Trigger mythos, white supremacist propaganda with a number of goals. Relying closely on public symbols, it sought to mission a Southern antebellum innocence onto the previous, whereas telegraphing absolute white energy onto the long run.

To that finish, Misplaced Trigger mythologists portrayed Accomplice leaders—males whose most notable contribution to historical past was armed protection of white of us’ proper to purchase, promote, and enslave Black individuals—as heroes. Nameless Accomplice combatants, forged in bronze and stone, stood sentry atop lofty pedestals that implicitly demanded public veneration. The Confederacy’s dishonorable combat for Black enslavement was tacitly rendered an honorable however misplaced trigger. On the town facilities, alongside avenues, and in myriad different public areas, these statues stood as fixed signifiers of racial terror. On courthouse lawns and statehouse grounds, they had been strategically erected to function reminders to Black of us that these establishments had no regard for them.

Black of us, then as now, implicitly and empirically understood how white supremacist symbols are inextricably linked to white terror violence, imbuing the atmosphere with harassment and intimidation, race-stamping public areas as immutably white, and emboldening anti-Black vigilantism. Civil rights activist, educator, and Charleston, South Carolina, native Mamie Garvin Fields grew up within the shadow of a statue that went up in 1887 depicting politician John C. Calhoun, a vocal and virulent racist who as soon as referred to as Black enslavement a “optimistic good.”

“Our white metropolis fathers wished to maintain what [Calhoun] stood for alive,” Fields acknowledged in her memoirs practically a century later. “Blacks took that statue personally. As you handed by, right here was Calhoun wanting you within the face and telling you, ‘N-----, you might not be a slave, however I'm again to see you keep in your home.’”

Black of us protested white supremacist symbols littering the panorama, a courageous danger underneath the often-lethal menace of Jim Crow, which those self same monuments monumentalized and made tangible. When the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in 1931 erected a “loyal slave monument”—a kind of Accomplice marker selling the insane concept that Black individuals had been happiest being enslaved by white of us—close to the West Virginia website of John Brown’s riot at Harpers Ferry, the NAACP demanded a pill be positioned close by to honor Brown, noting a counter was wanted to the “nationally publicized pill giving the Accomplice standpoint” and the rising motion of “copperheadism,” or Accomplice sympathy and slavery apologism. W. E. B. Du Bois, who wrote that the dedication occasion for the UDC’s monument had been a “pro-slavery celebration,” drafted the proposed wording for the Brown memorial, which referred to as the abolitionist’s riot “a blow that woke a responsible nation.” It was by no means erected, however the NAACP made its resistance recognized.

Mamie Garvin Fields described how she and different Black kids would “carry one thing with us, if we knew we'd be passing that method, in an effort to deface” the Calhoun statue in Charleston, to “scratch up the coat, break the watch chain, attempt to knock off the nostril—as a result of he appeared like he was telling you that there was a spot for ‘n-----s’ and ‘n-----s should keep there.’” Newspaper accounts catalog but extra protests utilizing defacement, as in 1888 when a statue of the determine of Justice positioned at Calhoun’s ft was discovered with “a tin kettle in her hand and a cigar in her mouth”; in 1892, when somebody painted the face of the Justice statue “lily” white; or in 1894, when a younger Black boy named Andrew Haig shot on the determine of Justice with a tiny pistol. A park keeper was finally employed to cease “the nuisances and depredations now dedicated by goats, boys and night time prowlers,” however apparently failed in that mission.

In 1895, the Calhoun statue was eliminated. A neighborhood newspaper article recounts how, because the statue was being lowered off its pedestal by a rope, a gaggle of Black boys watching close by “skillfully pasted Mr. Calhoun within the eye with a lump of mud.” The unique Calhoun’s plinth stood forty-five ft within the air. In 1896, a substitute Calhoun was erected on a pedestal some 115 ft off the bottom. Formally, the primary Calhoun statue was eliminated due to design flaws, however Fields contends that Black “kids and adults beat up John C. Calhoun so badly that the whites needed to come again and put him method up excessive, so we couldn’t get to him.” The determine was lastly eliminated for good on June 25, 2020.

Black protests in opposition to white supremacist symbols continued through the Civil Rights period, changing into much more overt. In 1966, after an all-white jury acquitted the white man who admitted to murdering Sammy Younge Jr., a Black scholar activist attending Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, hundreds of protesters congregated on the city’s central Accomplice marker, spray-painting its pedestal with Younge’s title and the phrase “Black Energy.” Lower than two years later, simply after the April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Black college students on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill expressed their grief and rage by dousing a campus Accomplice statue often known as “Silent Sam” in pink paint. After a younger Black man named James Cates was murdered by a white motorbike gang in 1970, Black college students rallied on the foot of the monument. In a call-back to these demonstrations, UNC-Chapel Hill scholar Maya Little would pour a mix of her personal blood and pink ink on the statue in April 2018, in an motion that presaged its toppling by protesters 4 months later, boldly and precisely stating that “the statue and all statues prefer it are already drenched in black blood.”

In these and much too many examples to explain right here, Black of us have protested the iconography of white energy from its earliest look, as a part of a broader motion towards the dismantling of white supremacy, writ giant. W. E. B. Du Bois, Mamie Garvin Fields, the early NAACP—all had been concerned in looking for rights for Black of us in numerous spheres, in calling out white supremacist socio-politics of their day. However in tandem with these efforts to safe Black of us’ civil rights, additionally they famous the best way these symbols tried to write down Black of us out of American historical past, and the way the online impact of symbols that conveyed anti-Blackness and white terror added gasoline to the prevalence of each.

This was by no means mere conjecture. The truth is, a 2021 research by researchers on the College of Virginia additional confirms it, concluding there's a direct correlation between Accomplice monuments and white racial terror, and that “the variety of lynching victims in a county is a optimistic and important predictor of the variety of Accomplice memorializations in that county.” These markers, most of which nonetheless stand, proceed to do the work of white supremacy. However there are hints of progress in acknowledging the harm they do, the hostile atmosphere they create, and the structural inequities their existence perpetuates. In late 2021, a Tennessee appeals courtroom granted a brand new trial to a Black man who had been convicted by an all-white jury who deliberated in a room filled with Accomplice memorabilia—together with a portrait of Accomplice president Jefferson Davis, a framed Accomplice flag, and a placard displaying the insignia of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The appellate courtroom’s jurists agreed with the argument that white supremacist symbology had an “inherently prejudicial” impression on jurors. Simply because the architects of the Misplaced Trigger had hoped they'd.

Writer

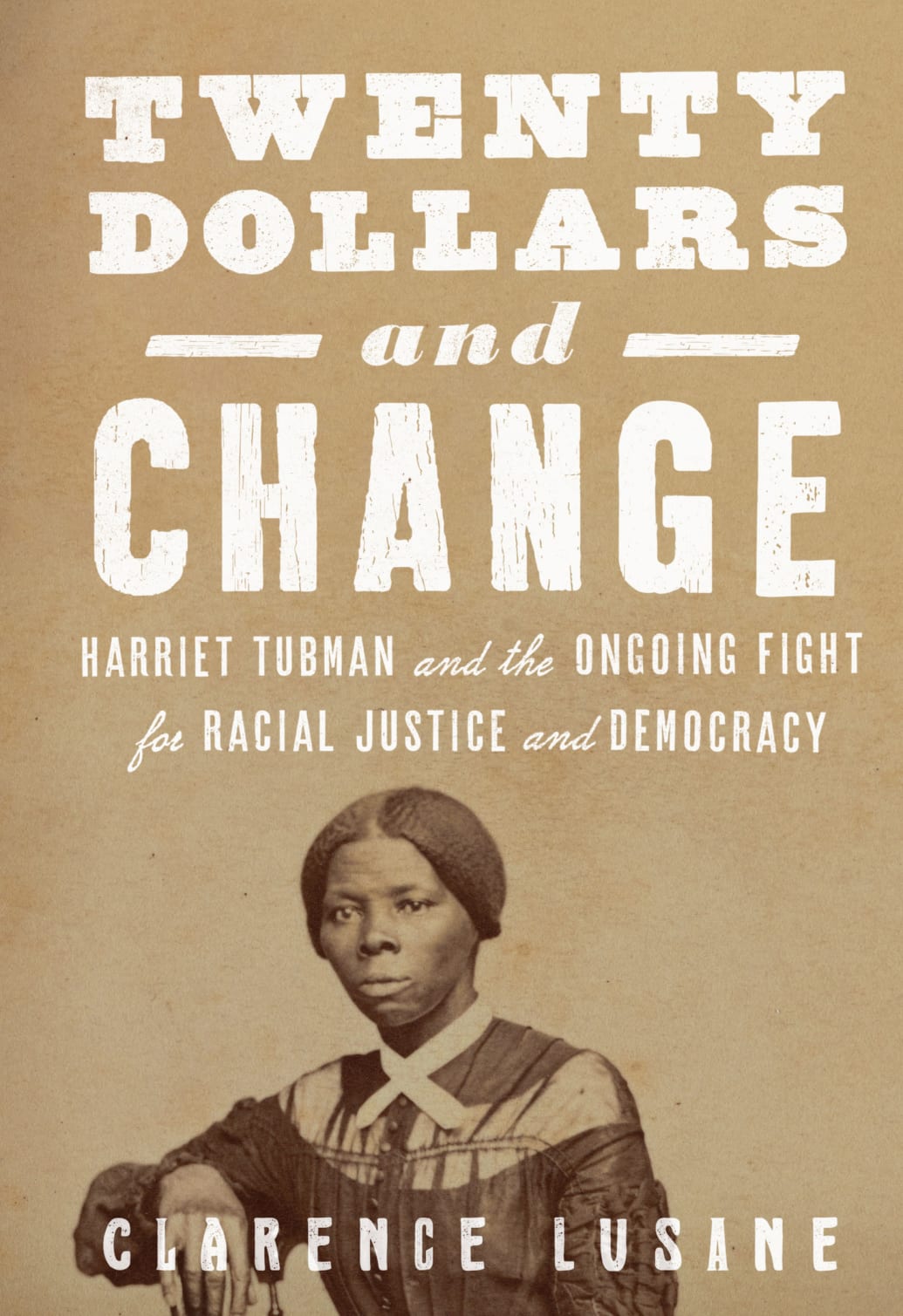

In Twenty Dollars and Change, scholar Clarence Lusane makes the identical argument in regards to the energy of symbols and their impression on public consciousness, however in its inverse, suggesting that the “inherently prejudicial” impact of the photographs we select can and must be used to reinforce bigger struggles for actual change. Utilizing the talk across the U.S. Treasury’s promise to interchange Andrew Jackson with Harriet Tubman on the entrance of a twenty-dollar invoice as a springboard, Lusane argues that “rolling out a Tubman twenty not solely disrupts and diminishes the legacies of white supremacy that persist in official narratives, however that doing so is a essential step towards diminishing and abolishing racist distortions of our political economic system, well being and medical establishments, and justice system.”

“For this reason the ebook is known as Twenty Dollars and Change,” writes Lusane: “it's an effort to handle the connection between official narratives and energy, and the pressing want to remodel each.”

What does it imply to have Tubman on the twenty, in addition to poet Maya Angelou on the quarter, as white supremacist legislators and white mother and father work in tandem to ban Angelou’s books and legally prohibit educating about slavery utilizing the mislabeled racist boogeyman of “vital race concept”? How will we reckon with the incongruity of placing Tubman and Angelou on cash whilst racial capitalism is instantly answerable for Black girls, who've the best labor drive participation price amongst girls, being paid 36 p.c lower than white males and 20 p.c lower than white girls, being 3 times as more likely to stay in poverty as white girls, and struggling the best job losses and financial struggling amongst all American girls amidst the coronavirus pandemic?

Extra broadly, Lusane elucidates how structural racism and the convulsive and round political violence of white backlash—embedded in modern Republican politics, anti-Black voting suppression, and resistance to laws that will restore the Supreme Court docket’s decimation of the Voting Rights Act; anti-protest legal guidelines, some permitting vicious assaults in opposition to demonstrators, handed at a quick clip after the anti-racist uprisings following the police homicide of George Floyd; and statutes in opposition to “wokeness” that concentrate on public colleges, libraries, and locations of labor—undermine the strides of Black progress. “It's the quotidian violence of America’s racial caste system,” writes Lusane, “that poses essentially the most vital menace to communities of coloration and democracy itself. Finally, it's that system, and the narratives that validate it, that have to be overthrown.” It's within the service of that purpose that Lusane additionally fastidiously, and contemplatively, contextualizes Tubman’s work and legacy as foundational to a convention of resistance, together with the fierce battle in opposition to the regressive anti-Black racism of this second. It is usually in service of that purpose that he advocates we make the acutely aware “inherently prejudicial” option to see an illiterate, handicapped, self-emancipated, rebel Black lady for the completely unique American icon—and hero—she is.

This, Lusane notes, is precisely why figures resembling Harriet Tubman and Maya Angelou, for all of the legitimate issues over empty efforts at racial inclusion, must be represented, centered, honored, and celebrated. The exclusion of Black of us, and significantly Black girls, from America’s public-facing pictures of itself—monuments, cash, and extra—has at all times been a warped reflection of whiteness wholly incongruous with the precise face of this nation. Sincere narratives about Black girls and folks who proceed to combat for what this nation purports to face for, saving America from its personal worst and most insidious tendencies, must be in our public areas and on our shared objects. In tandem with the work of change on the bottom and elsewhere, they're the totems of progress.

If illustration didn’t matter, the precise wouldn’t be preventing so exhausting to maintain all of it white.

Twenty Dollars and Change is a future-gazing information to who we have to be to turn into who we declare to be. And, as Lusane notes, we'll solely get there by altering, in and out.

Foreword by Kali Holloway excerpted from Twenty Dollars and Change by Clarence Lusane, copyright 2022 Clarence Lusane, printed and reprinted with permission of Metropolis Lights Books.