Picture Illustration by Thomas Levinson/The Every day Beast/Sony Footage

One of many best methods for a horror film to generate suspense is by making its characters wholly ignorant in regards to the menace they face—in order that, for instance, they’re unprepared to battle a vampire as a result of they don’t know what one is, a lot much less find out how to kill it.

It’s an inexpensive storytelling shortcut, and it’s one which’s doggedly employed by The Son, Florian Zeller’s follow-up to final 12 months’s The Father, whose total home drama hinges on the abject cluelessness of its parental protagonists. Solely tragedy can ensue when nobody is aware of about despair (its signs, its causes, its therapies), and ensue it most actually does, after two lugubrious hours of adults crying, fuming, and appearing like uninformed dolts.

Zeller’s The Father was a narratively astute and formally sharp portrait of dementia, which makes the author/director’s newest—as along with his prior work, an adaptation of his play of the identical title—a shocking misfire.

Debuting in theaters on Nov. 25, the movie is about in present-day New York, however, because of its topics’ old style attitudes and figurative blindness, feels prefer it takes place within the Nineteen Forties, earlier than anybody was conscious of and/or talked about scientific despair and chopping. That alone makes the proceedings really feel quasi-dreamlike, though that will merely be the byproduct of Zeller’s stilted staging and writing, each of which contribute to an artificiality that undercuts his many, many makes an attempt at heartstring-tugging.

Rekha Garton/See-Noticed Movies/Sony

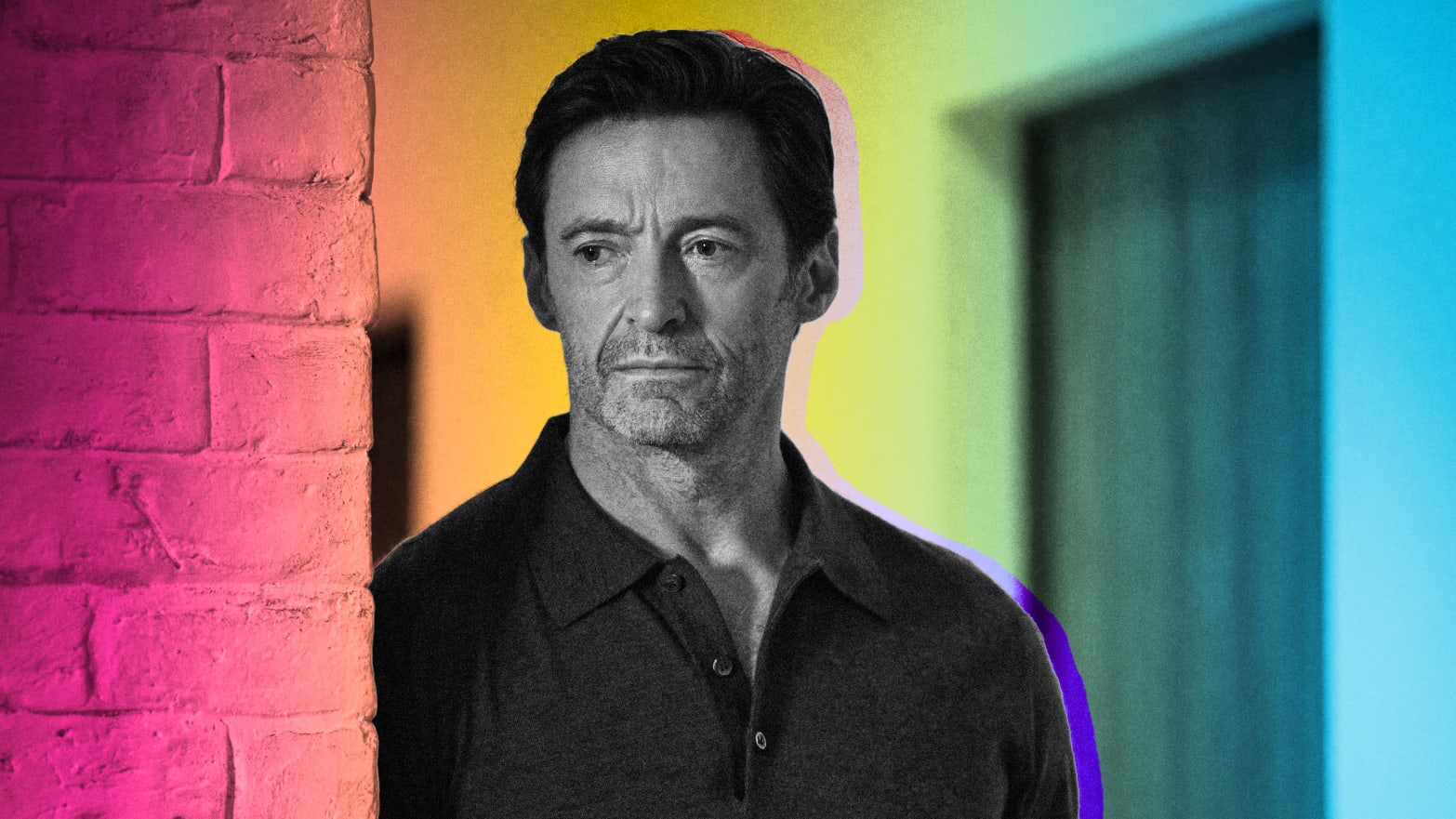

Although The Son opens with Beth (Vanessa Kirby) cooing a lullaby to her child boy Theo in his crib, the title of Zeller’s movie refers to Nicholas (Zen McGrath), the teenage son of Beth’s husband Peter (Hugh Jackman), whom he had with first spouse, Kate (Laura Dern).

Peter is a big-time lawyer who’s contemplating becoming a member of a pal’s political marketing campaign. Whereas he’s an outwardly cheery and charming fellow, he’s a workaholic who consistently places himself first and glosses over hassle with cheery platitudes. There’s rigidity on the corners of Jackman’s smiles, and the look in his eyes means that he understands greater than he lets on. He’s an apparent grasp of evasion and denial, and people abilities are put to the take a look at when Kate seems at his residence door with unnerving information: Nicholas has covertly skipped college for the previous month.

Peter and Kate are each distressed by this revelation, and confounded by Nicholas’ refusal to clarify why he’s spent his schooldays wandering Manhattan’s streets and parks—and, on prime of that, why he’s chopping himself. When Nicholas tells Kate that he needs to maneuver in along with his father, she’s devastated, however acquiesces, and Peter does his finest to welcome him into his dwelling. Sadly, that’s hardly a balm, because it’s readily obvious—at the least, to everybody besides these on this movie—that Nicholas is a deeply sad particular person nonetheless smarting from Peter “abandoning” his household for Beth, with whom he had an affair.

These dynamics are exacerbated by further elements, together with Kate harboring emotions for her former husband; Beth’s insecurity and resentment close to Kate; and Peter’s behavior of pretending that Nicholas is okay. (“All in all, it’s going effectively,”; “He’s making an effort”) Peter can be livid at his personal awful dad (Anthony Hopkins), who ditched him and his dying mom years earlier, and who, throughout a short reunion, tells his 50-year-old son to “simply fucking recover from it, please.”

These individuals’s tumultuous points are as plain as day, and but they do nothing however exhibit an epic lack of self-awareness. By the point Peter realizes that he’s turn out to be his absentee father, his obliviousness has reached nearly laughably monumental ranges. That goes double for his—and Kate, and Beth’s—dim-witted response to Nicholas’ anguish. Apart from one journey to the therapist, Nicholas receives no therapy for what's unmistakably despair; as a substitute, the well-to-do New York adults in his life reply as in the event that they’ve by no means heard of that situation, a lot much less thought of that Nicholas could be affected by it.

Their naivety is the movie’s as effectively, with Zeller having everybody converse in blunt trend—Nicholas about his grief and disinterest in life, which he can’t describe or clarify; Peter and Kate about their mystification over their son’s distress, which results in misguided and ineffective encouragement and threats—that will be proper at dwelling in an Afterschool Particular episode.

Zeller’s writing is leaden and his photographs are not any extra swish, self-consciously separating and isolating characters to underscore their selfishness and loneliness. The nadir of that may be a slow-motion lounge dance sequence that ends with a pan away from joyous Peter and Beth and towards sullen Nicholas.

Rob Youngson/See-Noticed Movies/Sony

Given the dexterousness of The Father, The Son’s clunkiness comes as one thing of a shock, and it’s compounded by McGrath’s efficiency. Jackman and Dern do their finest to deliver nuance to Peter and Kate’s panic and terror, even when that effort is basically futile, however McGrath isn’t as much as that process. His agonized outbursts are affected lowlights in a movie that’s too busy stating its each concept and manipulating its viewers with disingenuous plotting with a view to wring pathos from its child-in-crisis situation.

So clumsy and clear is The Son that it has Nicholas, completely out of the blue, casually deliver up Peter’s gun, lest anybody suppose that issues are going to prove okay for all concerned. The one reputable query hovering over Zeller’s movie is who will chew the (literal) bullet, though earlier than any reply can materialize, the author/director first levels a psychiatric-hospital confrontation between Nicholas, his mother and father, and a caring physician that’s as preposterous as it's exploitative. That doctor is the one individual on this saga that has his head on straight and isn’t afraid to talk fact to idiocy, so in fact he is forged apart to ensure that the nightmare to succeed in its predestined conclusion.

Zeller is so intent on producing crushing pathos that he discards actuality and logic in its pursuit, thereby negating the poignancy he seeks. A rigged sport through which witlessness and gracelessness conspire to result in calamity, The Son is a dramatic case of the ends failing to justify the means.