Photo Illustration by Kelly Caminero/The Daily Beast

On Aug. 1, 2007, bumper-to-bumper traffic blanketed the I-35 bridge over the Mississippi River in Minneapolis. It was an otherwise normal day during evening rush hour. Some commuters were likely listening to "Hey There Delilah" by the Plain White T’s, the No. 1 song in the country at the time; or maybe they were tuned into talk radio and getting updated on the early days of the Democratic and Republican presidential primaries. Suddenly, just after 6 p.m. local time, the bridge over the river collapsed. About 145 people were injured and 13 tragically lost their lives.

Once a marvel of the modern world, America’s roads, bridges and railways now do not even rank in the top 10 countries for infrastructure according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report. The Minneapolis bridge collapse was followed almost a decade later by the 2015 Amtrak derailment in Philadelphia. Another three years passed and a pedestrian bridge collapse killed six at Florida International University. There’ve been numerous smaller disasters caused by crumbling infrastructure.

With the recent signing of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law, the U.S. is about to go through the biggest overhaul to its infrastructure in several generations. But there are environmental costs to the retrofitting of our power grid, water supply, and transit systems. Building construction accounts for 38 percent of all global carbon dioxide emissions. According to the EPA, construction and demolition materials generate two times as much waste as all other kinds of municipal waste. A 2018 study found the construction industry accounts for 30 percent of all waste generated around the world.

As a result of America’s longstanding car culture, part of the solution lies with how we build our roads and bridges. There are a few big solutions that might deserve a closer look.

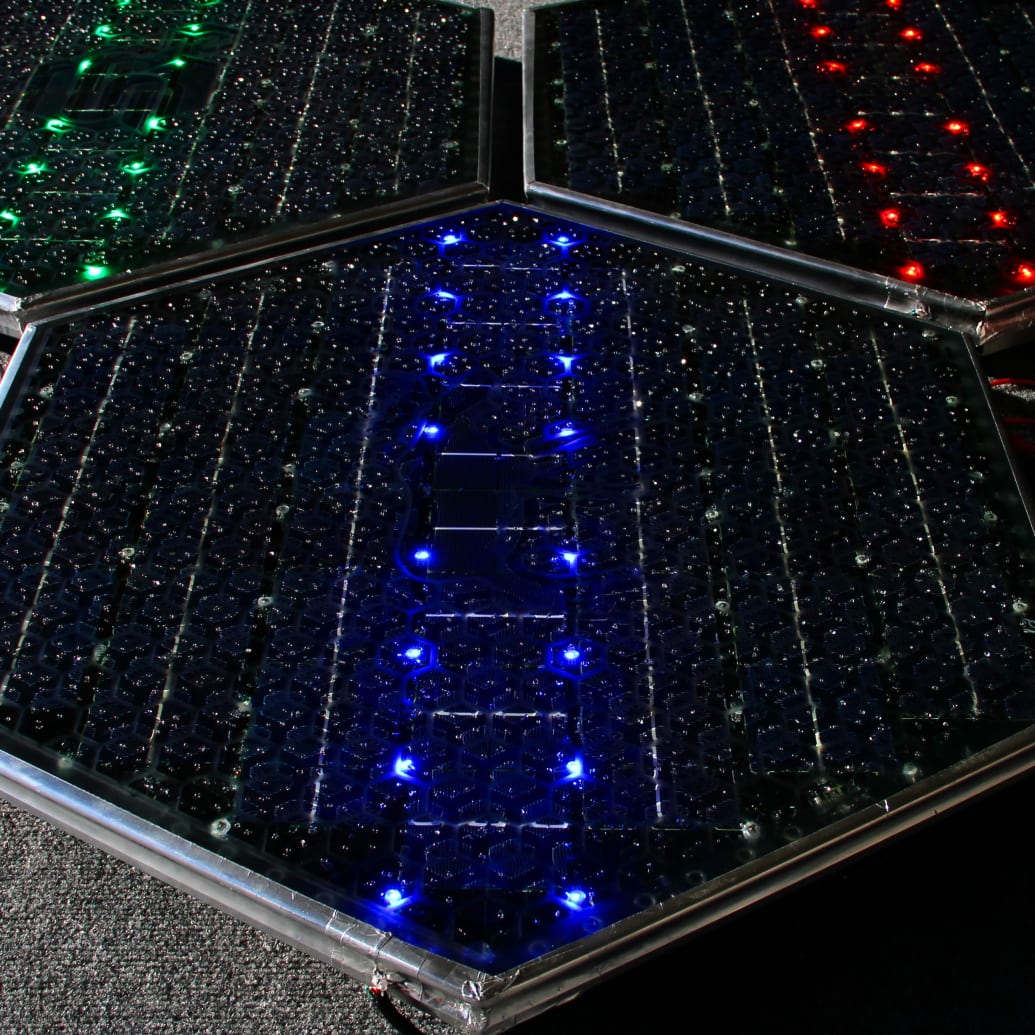

Photovoltaic Roads

Tucked away in the countryside in rural Idaho is a startup called Solar Roadways, pursuing the ambitious goal to replace America’s roadways and sidewalks with solar panels you can drive on. These photovoltaic roads could not only help make the roadway and its lighting self-sufficient, but also, the company claims, could power the entire country.

The technology is deceptively simple: Each roadway is made of interconnecting small hexagonal panels that are about 4 square feet in size. The panels collect solar rays and convert it into energy that powers lights and signs built into the roadway.

The panels can also power adjacent homes and businesses in nearby neighborhoods, creating a decentralized local grid so electricity does not need to be transmitted over long distances. This could be an especially intriguing safety net against large-scale grid failures like the ones experienced in Texas last winter and during the 2019 NYC blackout. Any additional power generated can be given back to the traditional power grid.

A three-panel prototype of Solar Roadways' photovoltaic roads.

Solar Roadways

Unlike solar panels installed alongside the road, Solar Roadways' panels are essentially part of the pavement. Because each panel is otherwise independent, it is easy to replace them quickly and without timely and expensive roadwork projects. Renovating just means replacing broken panels instead of filling potholes and resurfacing entire strips of the highway.

“If a panel is no longer communicating, I could throw one, since it’s only 70 pounds, in the back of my Subaru and drive out there and swap it out in five minutes,” Solar Roadways co-founder Scott Brushaw told The Daily Beast.

Although Brushaw’s company experienced some early success with funding (it received a $100,000 grant for a prototype from the Federal Highway Administration in 2014 and raked in more than $2.2 million from an Indiegogo campaign the same year), it’s taken years to fully demonstrate the panels can withstand stressors like heat waves, floods, and icy driving conditions. Solar Roadways finally expects to move into mass production next year.

“We’re working with a mass manufacturing company in Detroit, an automotive manufacturer that wants to take over the manufacturing of their panels, and they already have a warehouse set aside,” Brushaw said.

Installing photovoltaic roads is a time- and resource-heavy project, but Solar Roadways argues the electricity gains in the long run would offset those initial costs. The company claims its panels have a 23 percent power efficiency rate. Its current forecast suggests covering all of the country’s roads in photovoltaic panels could generate 23.7 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity.

This is just a fraction of the 3.8 trillion kilowatt hours the U.S. used in 2020. But the panels are only expected to get more efficient as the technology improves. Some of the newest solar panels set to come to market boast a 45 percent efficiency—a more than 25 percentage point increase since 2015.

The world's first solar road in Normandy, France.

Charly Triballeau / AFP via Getty Images

To be clear, there are other big limitations to photovoltaic roads that explain why Solar Roadways has been slow to get to mass production. Solar panels are less efficient when laying flat—hence the reason we often see them angled or shifting with the sun over the course of the day. On top of that, normal wear and tear will inevitably decrease efficiency.

The failure of other photovoltaic road projects underscore these challenges. A photovoltaic stretch of highway built in Normandy in December 2016 deteriorated within just two-and-a-half years. According to the French newspaper Le Monde, panels broke and failed to harness as much energy as advertised. Even comparable projects that have been successful are limited in scope, including a stretch of highway in Georgia called The Ray. Its panels cover an 18-mile stretch of I-85—a modest distance, nothing transformative. Solar Roadways’ success—or failure—is basically a make-or-break case study for photovoltaic road technology as a whole.

Electric Vehicles Are Ready for a Supercharged Boost

An effort that has received wider support from both the public and private sectors more broadly is a comprehensive electric vehicle (EV) charging network. This would include stations that dot the nation’s interstate highway system as well as on city streets across the nation.

As part of the proposed Build Back Better Plan (now in limbo after Sen. Joe Manchin withdrew his support), the Biden administration aims to install roughly 500,000 EV stations in the U.S. by 2030.

“If you're upgrading roads anyway, job one has got to be electric chargers along the side,” Bill McKibben, the famed environmental activist and the founder of environmental advocacy nonprofit 350.org, told The Daily Beast.

The Biden administration’s goal is to see half of all cars sold in the U.S. produce zero carbon emissions by 2030. Several automakers have made commitments to convert most, if not all, of their fleet of cars to EVs by this time, including Ford and GM.

An EV charging stations in a Walmart parking lot in Duarte, California.

Frederic J. Brown / AFP via Getty Images

A pivot to EVs doesn’t close off all sources of carbon emissions on its own. According to a 2019 report from the MIT Energy Initiative, the production of electric car batteries and fuel cells themselves actually generate more carbon emissions than manufacturing of traditional gas-guzzling vehicles— perhaps 40 percent higher, according to reporting from CNBC. And EV charge stations must still get their power from the local power sources, which often includes fossil fuels. California, the state with the largest EV market share, still gets two thirds of its energy from non renewable sources.

An expanded network of charging stations is critical to greater EV adoption. One of the biggest obstacles is how few and far between existing charging stations are throughout the country. There’s a robust presence of stations on the coasts and most major cities, but the absence of stations in huge parts of the American Midwest are preventing more consumers from switching to EVs.

Winning over those drivers would be a huge coup for combating climate change. Traditional single-occupancy vehicles used by most people to commute to work account for a damaging amount of global greenhouse gas emissions.

CONCRETE SOLUTIONS

Some conventional parts of how we build roads, highways, and bridges will linger through the decades no matter what kind of new technologies we adopt. And these things will still pose an environmental problem. According to clean energy research group BloombergNEF, using greener forms of concrete—even ones that are just 10 percent less carbon intensive—would be the equivalent of taking more than half a million combustion-engine cars off the road.

Concrete requires water and some form of filler like gravel to make a roadway or sidewalk. Gravel is usually obtained through mining, which can destroy neighboring ecosystems.

Sustainable materials company Arqlite, based in California, has developed an alternative to gravel made from upcycled plastic (a spinoff form of recycling where instead of breaking plastics down before remaking them into new goods, used plastics are directly turned into new products).

“We are really mining the landfill instead of mining a quarry,” Sebastian Sajoux, founder and CEO of Arqlite, told The Daily Beast. Arqlite’s material weighs three times less than other gravel alternatives, he said. That means truckers can pack more of the filler in their trucks bound for construction sites—which in turns means less trips hauling it around with large trucks and less carbon emissions spewed by those vehicles. It’s already being used by construction companies in all 50 states, according to the company.

Other companies are pursuing their own alternatives to traditional concrete. Grasscrete, based in the U.K., uses permeable materials that allow grass to grow through the concrete. That helps improve drainage and prevents polluted rainwater runoff from flowing into rivers, lakes and streams. This type of concrete was first introduced in the ’70s and has been used in places like Texas and Georgia, but there’s an opportunity to apply it more widely to America’s roads.

There are even some weirder concrete alternatives being studied, including concrete fillers made from mushrooms. In 2017, researchers at Rutgers University found that mixing Trichoderma reesei fungus sporesinto a concrete mix will protect pavement from wear and tear over time. When cracks appear, water permeates the surface and causes mushroom spores to germinate, which then produce calcium carbonate that plug up those cracks. It’s a far-off concept and one that has yet to pass muster to use in the real world, but it could be one extremely useful way to make regular road work a thing of the past.